Call US

24/7

Free Confidential case Evaluation

(813)922-0228Call US

24/7

Free Confidential case Evaluation

(813)922-0228Loading...

If you live in Largo, you know the feeling. You’re driving down East Bay Drive on a Tuesday afternoon, just trying to get home or maybe heading to the grocery store. Suddenly, traffic starts to slow down. You see the blue and red lights flashing ahead.

My heart always sinks a little when I see that. As an injury lawyer, I know what those lights usually mean. But as a neighbor and a member of this community, my stomach really drops when I see a teenager standing by the side of the road, looking terrified, phone in hand, staring at a crumpled bumper.

Teen driver accidents in Largo aren’t just a statistic on a government spreadsheet. They are happening right here, at the intersections we drive every day. I’ve had countless parents sit in my office, still shaking from the call they got an hour prior. They are worried about their child’s health, obviously. But once the dust settles, a new worry sets in. They start asking the hard questions about money, lawsuits, and their family’s future.

I want to have a frank conversation with you today. We need to talk about why our kids are crashing and the scary reality of who actually pays the price when they do.

People ask me all the time, "David, are drivers getting worse?" Honestly? It’s a mix of things. But for teenagers specifically, driving in Pinellas County is like being thrown into the deep end of the pool before you know how to tread water.

There are real reasons why we are seeing an uptick in crashes involving young drivers.

The "Conflict Points" Are Everywhere

Largo isn’t a sleepy town anymore. We have heavy commercial traffic mixing with residential neighborhoods.

Have you driven on U.S. 19 or near the Gateway Expressway project lately? It’s confusing enough for me, and I’ve been driving for decades. For a 16-year-old with six months of experience, shifting lanes, concrete barriers, and sudden stops are a recipe for disaster.

Places like Ulmerton Road and Seminole Boulevard are notorious. You have cars trying to beat yellow lights, people making U-turns, and tourists who don’t know where they’re going. These are "conflict points." An experienced driver knows to hover over the brake pedal here. A teen driver usually assumes the coast is clear until it’s too late.

The "100 Deadliest Days"

We hear this term in the safety industry, but it plays out consistently in Florida. The period between Memorial Day and Labor Day is dangerous. School is out. Teens aren’t driving to class; they are driving to the beach. They are driving to friends' houses. They are on the road later at night.

In Largo, this often means more kids in the car. And that is a huge factor. When a teen driver has two or three friends in the passenger seats, the risk of a fatal crash doubles. It’s simply too much distraction inside the vehicle to handle the chaos outside the vehicle.

Tech Is a Double-Edged Sword

We all know about texting. We hammer that into our kids’ heads. Don’t text and drive.

But the cases I’m seeing now involve different kinds of distractions.

GPS Apps: a kid looking down to see which turn to take for that new restaurant.

Streaming Music: trying to find a specific playlist on Spotify while merging onto Starkey Road.

Notifications: it’s not just texts. It’s Snapchats, Instagram alerts, and Life360 pings.

A two-second glance at a screen at 45 mph means they just drove the length of a football field blind. On our crowded roads, that’s usually where the brake lights of the car in front of them are.

Most parents assume that if their teen causes a crash, the insurance will handle it, and maybe their rates will go up. That’s the best-case scenario. But in Florida, the liability laws are very specific, and they are designed to protect the victim, not the driver or the driver's parents.

If you are a parent in Largo, you need to understand three concepts. These aren't just legal jargon; they are the things that can put your house and savings at risk.

You Signed the Contract (Statute § 322.09)

Do you remember the day you took your kid to get their learner’s permit or driver’s license? It’s a proud moment. You stood at the counter, filled out a form, and signed your name. Most people don't read the fine print on that form.

By signing that application, under Florida Statute § 322.09, you agreed to be jointly and severally liable for any negligence or willful misconduct of your minor child when they are driving.

This isn't about whether you own the car. This isn't about whether you were in the passenger seat. You essentially co-signed for their driving behavior. If they run a red light and injure someone, the law views you as equally responsible for the damages.

The "Dangerous Instrumentality" Doctrine

I know, it sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie. But Florida is one of the few states that follows this legal doctrine strictly. A car is considered a dangerous tool. Like a weapon. Because a car is dangerous, the law says the owner is responsible for how it is used. If you own the car, your name is on the title, and you give anyone permission to drive it, you are on the hook.

It doesn’t matter if you told your teen, "Drive safe."

It doesn’t matter if you said, "Don't take the interstate."

It doesn’t matter if you said, "Be home by 10."

If you gave them the keys (express permission) or even if they just took the keys and you didn't stop them (implied permission), you are liable. This catches so many parents off guard. They think, "I didn't crash the car, why am I being sued?" You are being sued because you are the owner of the dangerous instrument that caused the harm.

The "Permissive Use" Trap

This one gets complicated. Let’s say you let your son drive the car. He goes to a friend’s house. Then, he lets his friend drive your car to the store. The friend crashes. Are you liable?

In many cases, yes. Florida courts have often ruled that if you allow someone to use your car, and they allow a third person to use it, the owner is still responsible. You lose control of the liability the moment those keys leave your hand.

If you are driving around Pinellas County with the state minimum insurance coverage, you are walking a financial tightrope without a net. Florida’s "No-Fault" law can be confusing. People hear "no-fault" and think, "Oh, I can't be sued."

That is absolutely wrong.

"No-Fault" just refers to the first $10,000 of medical bills (PIP). That money gets burned through in about four hours in an emergency room. Once the injuries step outside that $10,000 window, which happens in almost every crash involving broken bones, whiplash, or concussions, the at-fault driver is personally liable.

If your teen causes a serious accident, the damages could be $50,000, $100,000, or more.

If you only have minimal coverage (like $10,000 in bodily injury), the insurance company cuts a check for that $10k and walks away. Guess who is responsible for the remaining $90,000

You are.

If you own a home, have a savings account, or have a job, those assets are now targets. I have seen families devastated financially because they tried to save $30 a month on their premiums and got caught in a bad teen driving accident.

Here is what I tell my friends and neighbors when they ask for advice. Review Your "Bodily Injury" Limits. Pull out your policy today. Look at the line that says Bodily Injury Liability. If it says 10/20 (meaning $10k per person / $20k per accident), change it immediately.

You want enough coverage to protect your assets.

I generally recommend at least 100/300 coverage if you are a homeowner, and an "umbrella policy" on top of that if you have significant equity or savings. Umbrella policies are surprisingly cheap and offer a million dollars or more in protection.

Florida has one of the highest rates of uninsured drivers in the country. If a drunk driver or someone with no insurance hits your teen, your own UM coverage is the only thing that will pay for your child’s medical bills and pain and suffering. Do not waive this coverage.

Create a Parent-Teen Driving Contract. Make it formal. Sit down and write out the rules.

No passengers for the first 6 months.

The phone goes in the glove box, or "Do Not Disturb" mode is on.

No driving after 10 PM.

If grades drop, the keys get taken away.

Make them sign it. It reinforces that driving is a privilege, not a right.

Ride With Them (Even After They Get Their License). Don’t stop coaching just because they passed the test. The test in the parking lot is nothing like driving on West Bay Drive at 5:00 PM. Ride with them occasionally. Watch their habits. Are they following too close? Are they braking late? Correct them now before it turns into a crash.

Look, nobody wants to call a lawyer. I get it. We are usually the last people you want to talk to because it means something went wrong. But if you get that call, and your teen has been in an accident, you need to be careful.

We have been handling cases in Largo and throughout Pinellas County for a long time. We know the local judges, we know the roads, and we know how to protect your rights. If you are worried about a crash, or if you just have questions about your liability as a parent, my door is open. We can sit down, look at what happened, and figure out the best path forward to keep your family safe and financially secure.

I’ve lived in Largo a long time. I’ve driven these roads every day. And I’ve sat across my desk from folks just like you who are upset, hurt, and confused. The first thing everyone asks me is, "David, how can they just leave? And who is going to pay for this mess?"

Florida law is tricky, and insurance companies are even trickier. But if you keep your head cool and follow the right steps, we can fix this. I’ve handled enough of these cases in Pinellas County to know exactly what works and what ruins a case.

Here is my guide on what you need to do immediately after a hit-and-run in Largo.

I know what your gut tells you. I really do. You see those taillights fading away, and the anger boils up. You want to slam on the gas. You want to catch them. You want to get that license plate number so bad you can taste it.

Don’t do it.

I have seen good cases fall apart because a victim decided to play vigilante. First off, it is dangerous. If that driver was willing to commit a felony by leaving the scene of a crash, you have no idea what else they are willing to do. Maybe they have a warrant. Maybe they have a weapon. Maybe they are drunk. You do not want a confrontation on the side of the road on US 19.

Second, it hurts your legal case. If you speed to catch them and you end up clipping another car, or you run a red light, the insurance company and the police might turn the tables on you. They’ll say you were driving aggressively.

Just let them go. It hurts to say that, but your safety is worth more than the satisfaction of catching them yourself. Pull your car over. Get out of the travel lanes if you can. Find a safe parking lot or a wide shoulder. Take a breath.

This is the biggest mistake people make. They get out, look at their bumper, see a dent, and think, "Well, the guy is gone. The cops won't catch him. I just want to go home."

So they leave.

If you do that, you might be throwing away thousands of dollars.

Here is the deal with Florida insurance. Since the other driver fled, we don't know who they are. We can't sue them directly yet. That means we are likely going to be filing a claim under your own Uninsured Motorist (UM) coverage.

Most insurance policies have a strict rule for UM claims, you must report the hit-and-run to the police within 24 hours.

If you don't call the police, the insurance adjuster is going to look at your claim and say, "How do we know another car hit you? Maybe you backed into a pole at the Wawa. Maybe you scraped a guardrail."

Without that police report, it’s your word against their skepticism. And insurance companies are professional skeptics.

Is anyone hurt? Is the road blocked? Is your car smoking? Call 911. Don't hesitate.

Is everyone okay, and are you safely off the road? Call the Largo Police Department Non-Emergency line at (727) 587-6730.

Wait for the officer. I know it’s hot. I know you’re stressed. But wait. When they get there, tell them,"I was hit by a vehicle that fled the scene."

Make sure you get the case number from the officer before they drive away. That number is the golden ticket for your insurance claim.

Since the bad guy is gone, the evidence is disappearing by the second.

Rain is common here in the afternoons. It washes away fluid leaks. Other cars drive over skid marks. Witnesses get bored and leave. Until I can get my team involved, you are the lead investigator on the scene.

Pull out your phone. Start snapping photos. But don't just take a picture of your bumper. Think bigger.

Look closely at where you were hit. Is there a smudge of red paint on your silver car? Take a close-up of that. That proves another vehicle was involved.

Look at the road. Is there a pile of broken plastic? A shattered headlight cover that doesn't belong to your car? Photograph it. If it is safe to do so, pick it up and keep it. I once had a case where we identified the make and model of a fleeing truck because we found a piece of its grill on the road.

Did they peel out? Take a picture of the tire marks. It shows speed and direction.

This is the modern age. There are cameras everywhere. Look around you.

Are you near a gas station?

Is there a bank on the corner?

Is there a traffic light with cameras on the arm?

Did you pass a Tesla (they record everything)?

Write down exactly where you are. If you come to me and say, "David, the crash happened right in front of the Publix on Ulmerton," I can act fast. I can send a legal "preservation letter" to that store immediately to stop them from deleting the security footage. But these places often wipe their tapes every 48 hours. We have to move fast.

If someone stopped to see if you were okay, ask them what they saw. Did they see the other car? Did they get a partial plate? Do not let them leave without getting their name and cell number. A neutral witness is the most powerful weapon we have in court.

I cannot stress this enough. This is where the Florida legislature really put the squeeze on drivers.

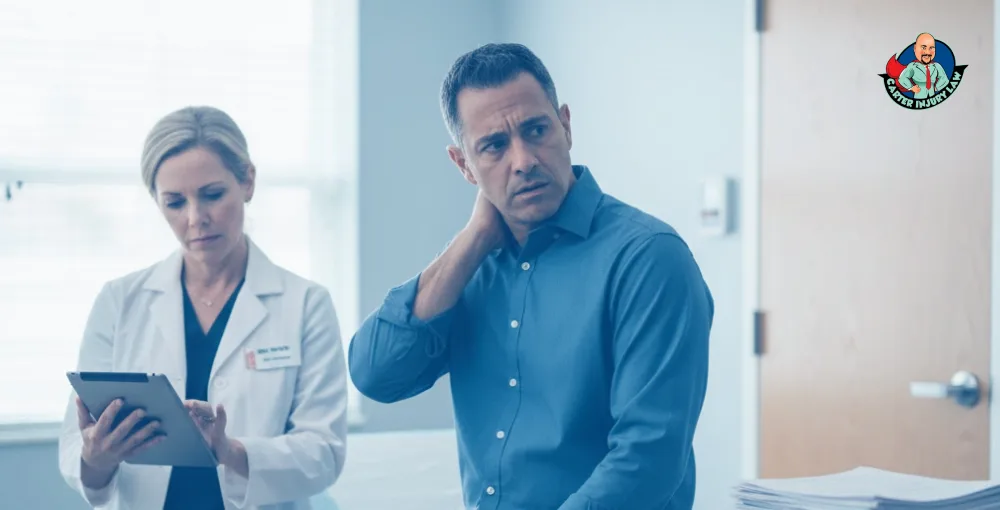

You might feel okay right now. Adrenaline is a powerful drug. It masks pain. You might think you’re just a little stiff. You figure you’ll take some Tylenol and sleep it off.

Please, go to the doctor.

Florida has a "14-Day Rule" for Personal Injury Protection (PIP). PIP is that coverage you pay for that covers 80% of your medical bills up to $10,000, regardless of who was at fault.

But If you do not seek initial medical care within 14 days of the crash, you lose that $10,000 coverage entirely.

Poof. Gone.

If you wait two weeks because you’re "toughing it out," and then on Day 15 you realize your neck hurts too much to work, you are out of luck. The insurance company keeps the money.

You don't have to make a big scene. You don't have to go to the ER if it’s not an emergency. But you need to get checked out.

ER: If you hit your head or have sharp pain, go to HCA Florida Largo Hospital.

Urgent Care: If it’s just soreness, go to Concentra or MD Now.

Just get it documented. Tell the doctor, "I was in a car accident." That creates the paper trail we need to unlock your benefits.

You have to call your insurance company. Most policies say you have to report a crash "promptly." Usually, that means within 24 hours for a hit-and-run.

But you need to be on guard. In a hit-and-run case, your insurance company becomes the adversary.

Since there is no other driver to sue, your insurance company has to pay out the claim. That means they lose money if they pay you. So, their goal, whether they admit it or not, is to pay you as little as possible.

They will try to trap you.

They will ask, "Are you injured?" If you say "No" or "I'm fine" because you haven't seen a doctor yet, they will record that. Later, when your back locks up, they will play that tape back and say, "But you said you were fine."

They will ask for a recorded statement. They act like it’s mandatory. They act like they can't help you until you give it.

Do not give a recorded statement.

You are not required to give a recorded statement immediately. You can simply say this:

"I have reported the accident. I was hit by a vehicle that fled. Here is the police case number. I am going to see a doctor. I will not be giving a recorded statement until I have spoken with my attorney, David Carter."

That stops them cold. It buys us time to make sure you don't accidentally say something that ruins your case.

You might be thinking, "David, can't I just handle this myself? It seems straightforward."

I wish it were. But Uninsured Motorist claims are some of the hardest fights in the business.

The insurance company will look for any reason to deny the claim.

They will say the damage to your car isn't "consistent" with a crash.

They will say your injuries are from "degeneration" or "old age," not the accident.

They will offer you a check for $500 and ask you to sign a release.

Don't sign it. Once you sign that release, you can never ask for another penny, even if you need surgery six months from now.

You need someone who knows the game. You need someone who knows that the intersection of 113th and Bryan Dairy is a hotspot for crashes. You need someone who knows which orthopedic doctors in Largo will wait for payment until the case settles, so you don't have to pay out of pocket.

A hit-and-run makes you feel powerless. It makes you feel like a victim. But you don't have to stay a victim. You have rights, and you have neighbors like me who are ready to stand up for you.

Take a deep breath. We’ll get through this.

If you are about to make that phone call to your insurance agent, stop for a second. I can give you a simple script to read so you don't say the wrong thing. Just ask, and I’ll break it down for you.

If you are reading this right now, I am guessing that scenario isn't hypothetical for you. It’s your reality. Maybe you’re sitting in the ER waiting room at Largo Medical Center, or maybe you’re at home, staring at a wrecked car in the driveway and a pile of insurance forms on the kitchen table.

First off, take a breath. Seriously.

I’m David Carter. I run Carter Injury Law right here in town. I drive the same roads you do. I know that the construction on US-19 is a mess and that the intersection at East Bay and Starkey is a disaster waiting to happen. I also know that right now, you pulled out your phone, typed "Largo car accident lawyer near me" into Google, and got hit with a million results. Billboards. TV jingles. Screaming ads promising you millions of dollars in five minutes. It’s a lot of noise.

I want to help you cut through that noise. I’m writing this not just to tell you to hire me, though I’d be honored if you did, but to teach you how to hire a lawyer in Pinellas County.

Let’s be real about something. When you search for a lawyer online, a lot of the big names you see don’t actually live here. They don’t work here. They might have a "satellite office" in a strip mall somewhere that is unstaffed 90% of the time, but their headquarters are in Orlando, Miami, or even another state.

They are marketing machines. To them, Largo is just another data point. Just another zip code to target with ads.

Why does this matter to your case?

Personal injury law isn't just about knowing the statutes; it’s about knowing the people. It’s about knowing the judges at the Pinellas County Justice Center. It’s about knowing how local juries tend to react to certain types of cases. It’s about knowing which insurance defense attorneys in Tampa Bay are reasonable and which ones like to play games.

When I walk into a negotiation or a courtroom, I’m on my home turf. I know the local police officers who wrote the accident report. I know the reputation of the chiropractors and orthopedic surgeons in the area.

If you hire a firm based in Miami to handle a crash that happened on Seminole Boulevard, they are playing an away game. They don’t know the lay of the land. They don’t know that the traffic light at that specific intersection has a history of malfunctioning or that the sun glare at 5:00 PM makes it impossible to see westbound traffic.

This is one of the things that frustrates me the most about my industry, and it’s something you need to watch out for.

You call a big, flashy law firm. You get a person on the phone who sounds incredibly sympathetic. They tell you exactly what you want to hear. You sign the digital contract. You feel relieved.

And then... silence.

Or worse, you call back to ask a question about your medical bills, and you can’t get the attorney on the phone. Instead, you get a "Case Manager." Or a "Client Liaison." Or a paralegal’s assistant.

You realize, with a sinking feeling, that you are never going to talk to the guy whose face is on the billboard. You are just a file number in a massive stack on someone’s desk.

I run things differently. I take it personally.

I believe that if you hire David Carter, you should get David Carter. I’m the one who reviews the evidence. I’m the one who builds the strategy. And when you have a question about whether you should accept a settlement offer or push for more, I’m the one you’re going to talk to. When you are vetting attorneys, ask this question: "Will I have your direct email address and phone number?"

If they hesitate, that’s a red flag.

Here is a dirty little secret of the insurance world, Insurance companies keep score.

They have databases on every injury lawyer in Florida. They know exactly who is willing to go to court and who is terrified of it.

There are some firms, we call them "settlement mills," that operate on volume. Their business model is to sign up as many people as possible, do the bare minimum amount of work, and settle the case for whatever the insurance company offers first. They want a quick turnover. They want their fee, and they want you out the door so they can bring the next person in.

Insurance companies know who these lawyers are. When they see a letter from a settlement mill, they lowball the offer. Why? Because they know that lawyer will never, ever file a lawsuit. They know that lawyer will pressure you to take the tiny check just to close the file.

Then there are trial lawyers.

Now, I’ll be honest with you: Most car accident cases in Largo settle before they ever get to a jury trial. That’s normal. But the reason they settle for a fair amount is the threat of a trial.

If the insurance company knows that I am willing to file a lawsuit, take depositions, and drag them into a courtroom to explain themselves to a jury, they get scared. Trials are expensive for them. They are risky. They would much rather write a fair check now than face me in court later.

You want a lawyer who has "courtroom cred." Even if your case never sees the inside of a courtroom, you need a lawyer who prepares as if it will. That is the only way to get maximum value for your injuries.

You’ve heard it a million times: "No recovery, no fee." "We don't get paid unless you get paid."

It sounds great, and it is. It’s called a contingency fee, and it’s the standard for almost all personal injury lawyers in Florida. It allows regular folks to hire top-tier legal talent without having to pay thousands of dollars upfront.

But, you need to read the fine print.

While the fee (the percentage of the winnings) is standard, usually 33.3% if we settle before a lawsuit and 40% if we have to file suit, the costs can vary.

"Costs" are things like filing fees with the court, paying for medical records, hiring accident reconstruction experts, or paying for court reporters. Some firms will try to charge you for "administrative fees" or "postage and copy costs" even if they lose your case.

That’s not how I do business.

I sit down with you and explain the contract line by line. No hidden junk fees. No surprises at the end of the case. If we don't win money for you, you don't owe me a dime for my time. Period.

If you were just in a crash in Largo, your adrenaline is probably still pumping. You might be confused about what to do next. Here is a quick checklist from a lawyer’s perspective.

Florida law has a "14-Day Rule." 1 You need to seek medical treatment within 14 days of your accident to access your PIP (Personal Injury Protection) benefits. Even if you think you’re just "a little sore," go to a doctor. Go to an urgent care on West Bay, or see your primary care doctor.

Whiplash often doesn't hurt bad until two or three days later. If you wait too long to see a doctor, the insurance company will say, "Well, he didn't go to the doctor for three weeks, so he must not have been hurt that bad." Don't give them that ammunition.

You have to talk to the police to get a report. Be honest with them. But what if the other driver's insurance company calls you? Hang up.

They are recording the line. They are trained to ask trick questions. They will ask, "How are you feeling today?" And if you say, "I'm okay," they will use that soundbite later to prove you weren't injured.

Tell them, "I am going to hire an attorney. All future communication goes through them." Then stop talking.

If you can, take pictures. Pictures of your car, their car, the road, the skid marks, the bruises on your arm. In the age of smartphones, there is no excuse for lack of evidence. This stuff is gold when I’m building your case later.

People sometimes ask me why I chose personal injury law. They ask why I want to deal with car crashes and insurance companies all day.

The simple answer is, I hate bullies.

And let’s be clear, most insurance companies act like bullies. They are billion-dollar corporations that have entire departments dedicated to paying you as little as possible. They deny valid claims. They delay payments, hoping you’ll get desperate. They try to blame you for an accident that wasn't your fault.

I see my job as leveling the playing field.

If you are still reading, you probably have a lot of questions specific to your crash.

Whose fault was it?

How will I pay for my rental car?

How much is my case worth?

I can’t answer those here. Every crash is different. A rear-end collision on the Howard Frankland Bridge is different from a T-bone on Walsingham Road.

So, here is my offer to you. Call my office.

We can sit down or hop on a Zoom call if you’re not up to traveling and just talk. It’s a free consultation. I’ll look at your accident report, I’ll listen to your story, and I’ll give you my honest opinion.

If I don’t think you need a lawyer, I’ll tell you. If I think another lawyer is a better fit for your specific issue, I’ll tell you that too. But if I think we can help you, I’ll explain exactly how we’re going to fight for you.

If you live in Largo, work in Pinellas Park, or just commute through the heart of the county, I don’t even have to finish the sentence. You know the groan that happens when someone mentions Ulmerton Road.

It’s the headache of Pinellas County. It’s the road where "just running a quick errand" turns into a white-knuckle experience.

I’ve been practicing law here for a long time at Carter Injury Law. I live here. I drive these roads just like you do. And from where I sit, looking at accident reports, talking to injured clients, and dealing with insurance adjusters, Ulmerton Road (State Road 688, if we’re being formal) isn’t just annoying. It is consistently one of the most dangerous stretches of pavement in our area.

So, let’s talk about it. Let’s break down why Ulmerton Road has so many accidents, what I see in my office, and how you can keep yourself (and your car) in one piece.

There is a term urban planners use that fits Ulmerton Road perfectly. It’s ugly, but it’s accurate. They call it a "Stroad."

It’s a mix of a street and a road.

A "road" is supposed to be for high speed. Think of I-275 or US-19. Its job is to move cars from Point A to Point B fast. A "street" is supposed to be where life happens, shops, restaurants, driveways, and people walking.

Ulmerton tries to be both, and that is why it fails.

We have speed limits that say 45 or 50 mph (which means folks are actually doing 60), but the road is lined with hundreds of driveways, gas stations, fast-food joints, and strip malls. You have traffic trying to flow like a highway, mixing with grandma trying to turn right into a Walgreens.

Beyond the engineering, there are factors that are just native to living in Largo and Pinellas County. You can’t ignore these.

Ulmerton runs almost perfectly east to west. If you have lived here longer than a week, you know what happens during rush hour.

Morning Commute (Eastbound): You are driving straight into the rising sun. It’s blinding.

Evening Commute (Westbound): You are driving straight into the setting sun.

I have handled cases where the driver truly, honestly did not see the car stopped in front of them because the sun glare was like a laser beam in their eyes. Visors don’t help. Sunglasses barely help. When you combine that glare with the stop-and-go traffic near Seminole Blvd, reaction times drop to zero.

Look, we love our winter residents. They support our local businesses. But we have to be real about the traffic impact. From November to April, the volume on Ulmerton explodes.

You have locals who know exactly which lane they need to be in mixing with visitors who are looking at their GPS, trying to find their rental condo, and suddenly realizing they need to make a U-turn. That hesitation causes rear-end accidents. It causes sideswipes. It frustrates the locals, leading to aggressive driving, which just makes everything worse.

When I review accident data or take calls from new clients, there are specific intersections that come up over and over again. If you are driving through these spots, you need to be on "high alert."

This area is a magnet for rear-end collisions. Why? Because everyone is trying to get somewhere specific. You have the mall entrance, the movie theater, the restaurants, and two major intersections back-to-back.

Traffic bunches up here. You think traffic is moving, and then suddenly everyone stops dead because the light at 113th turned red. If you are looking at your phone here, you are going to hit someone.

This is a massive intersection. It feels like crossing an ocean. The issue here is red-light running. The cycles of light are lengthy. No one wants to endure yet another cycle. People floor it when that light turns yellow. However, the other side has a green light by the time they cross because the intersection is so wide.

When the light turns green for you at 49th, wait a beat. Look left. Look right. Ensure the guy in the pickup truck trying to beat the yellow actually stops.

Another heavy hitter. We see a lot of "left-turn" accidents here. Drivers get impatient waiting for the arrow, or they try to shoot the gap on a solid green. If you turn left in front of oncoming traffic, it is almost impossible to prove you weren't at fault. Just wait for the arrow.

I want to get a little technical for a minute with "liability" talk. These are the specific behaviors on Ulmerton that get people sued.

I see this constantly near the industrial parks on Ulmerton. Traffic is backed up in the left and center lanes. Someone is trying to pull out of a gas station to turn left. A "nice" driver in the left lane stops and waves them through.

The driver pulls out, thinking it’s clear. But the driver in the right lane didn’t stop. They didn’t wave anyone through. They are doing 50 mph. And the next thing I see is a T-bone collision.

Do not be polite. Be predictable. If you have the right of way, take it. Stopping to let someone in when traffic is moving is dangerous. If you wave someone into a crash, you can actually be dragged into the liability mess.

Ulmerton has wide turns. Drivers turning right on red are looking left at the oncoming traffic. They are watching for a gap. They see a gap, hit the gas, and turn right. What they didn’t look at was the crosswalk to their right. We handle cases where pedestrians are hit this way. The driver says, "I never saw him." Well, you didn’t see him because you were only looking for cars.

If you are turning right on red, you have to stop completely. Look left, look right, and look left again.

I don’t want you to have to call my office. I mean that. I’m happy to help when things go wrong, but I’d much rather you go home to your family safe and sound. Here is what I tell my friends and family about driving on Ulmerton Road.

This is the single best piece of advice I can give you. Accidents on Ulmerton are messy. It’s often "he said, she said."

Without a witness, it’s a fight. A $50 dashcam solves that fight in five seconds. It is the cheapest insurance you will ever buy. If you drive in Pinellas County without one, you are taking a huge risk.

You learned the "two-second rule" in driver’s ed? Forget it. That’s for perfect roads with perfect drivers. On Ulmerton, you need three or four seconds of space. Rear-end collisions are the most common crash we see.

In Florida, there is a "rebuttable presumption of negligence" if you hit someone from behind. That’s fancy lawyer talk for: It’s your fault unless you can prove a miracle happened. Leave space. If people cut in front of you (and they will), just let off the gas and make space again. Let them win. It’s not a race.

If you don’t have to be in the right lane, don’t be. The right lane is where people are slamming on brakes to turn into Wendy’s. It’s where people are pulling out slowly from tire shops.

The middle lane is usually your safest bet for through-traffic. The left lane is okay, but you have to watch for people stopping to make U-turns.

Find your lane, stay in it, and avoid weaving. The weavers are the ones who end up flipping their cars.

This goes for drivers and pedestrians. If you are walking across Ulmerton, assume the cars cannot see you. The lighting in some spots is terrible, and with the distractions of phones and touchscreens, drivers aren’t scanning for people.

If you are driving a motorcycle, this goes double for you. Ulmerton is tough for bikers. People just don't look for the single headlight.

Ulmerton Road isn’t going anywhere. We are stuck with it. It’s a vital artery for our community, but it demands respect. It’s crowded, it’s fast, and it’s full of distractions. But if you understand why it’s dangerous, you can drive it defensively.

Drive like everyone else is distracted. Drive like everyone else is late. Give yourself extra time so you aren’t the one speeding to beat the light at 66th Street.

And if the worst happens, and you find yourself on the side of the road with crushed metal and a hurting back, you know where to find me. I’ve seen it all before on this road, and I’m here to help you pick up the pieces.

I want you to know two things right away. First of all, you are not insane. Biologically, delayed neck or back pain following a car accident is extremely common.

Second, and this is the hard truth, Florida’s insurance laws are designed to punish you for waiting.

I’m David Carter, founder of Carter Injury Law. I’ve spent my career fighting for folks here in Florida who get tangled up in our complicated insurance system just because they didn’t feel pain the exact second a crash happened.

If you are feeling delayed symptoms right now, you need to understand that the clock is already ticking against you.

Before we get into the legal weeds, let’s validate what you’re feeling medically. Why does delayed onset muscle soreness or whiplash happen?

When a multi-ton vehicle slams into yours, your body goes into instantaneous survival mode. Your brain floods your system with a cocktail of adrenaline and endorphins. These are powerful chemicals designed for a "fight or flight" situation. They do an incredible job of masking pain signals so you can function in a crisis.

Think of it like a football player who breaks a finger during a big play but doesn't feel it until he's sitting on the bench ten minutes later.

It’s only after the dust settles, the police report is filed, and you’ve tried to return to normal life, usually 24 to 72 hours later, that the adrenaline wears off. That’s when inflammation sets in. The soft tissues in your neck and back, which were violently stretched during the impact, start screaming.

Unfortunately, insurance companies love to ignore this biological reality. They see that police report where you said, "I'm fine," and they try to use it as a get-out-of-jail-free card.

To understand why delayed pain is such a problem here, you have to understand Florida’s weird insurance setup. We are a "no-fault" state.

This confuses a lot of people. It doesn't mean the other driver isn’t at fault for hitting you. It just means that no matter who caused the wreck, your own car insurance is responsible for paying your initial medical bills and some lost wages.

This coverage is called Personal Injury Protection, or PIP. If you drive in Florida, you are required to carry at least $10,000 of it.

The idea behind PIP was to make things faster. You get hurt, your own insurance pays, and we avoid clogging up the courts with small lawsuits. In theory, it sounds great. In practice, the insurance lobby has managed to pass laws over the years that make accessing those benefits harder and harder, especially for people whose injuries aren't immediately obvious, like broken bones.

If you take only one thing away from this article, make it this section. This is where folks with delayed back pain get burned the most often.

Under Florida Statute § 627.736, there is a strict deadline on your PIP benefits.

To be eligible for any of your PIP coverage to pay your medical bills, you must receive initial medical care within 14 days of the date of the motor vehicle accident.

Notice it doesn't say "14 days from when you started hurting." It says 14 days from the crash.

I cannot tell you how many heartbreaking consultations I’ve had where someone tried to tough it out. They used heating pads, they stretched, and they hoped it would go away. They finally couldn't take the back pain anymore and went to an urgent care center on Day 15.

At that point, their own insurance company is legally allowed to deny their PIP claim entirely. They are left on the hook for 100% of those medical bills.

Don't let that happen to you. Even if you think it's just minor stiffness right now, you need to get it documented by a professional immediately to stop that 14-day clock. You can see:

A Medical Doctor (MD)

A Chiropractor (DC)

A Dentist (for jaw pain/TMJ related to the crash)

An emergency room or urgent care facility

Okay, so you made it to the doctor within 14 days. You’re safe, right? You get your $10,000 in medical coverage?

Not necessarily. This is the second trap Florida law sets for delayed injuries.

Just seeing a doctor in time isn't enough to guarantee full benefits. Florida law creates two tiers of PIP coverage based on the severity of your diagnosis.

The Full $10,000: You only get access to the full policy limit if a medical doctor, osteopathic physician, dentist, or advanced nurse practitioner determines that you have an "Emergency Medical Condition" (EMC).

The $2,500 Cap: If you see a doctor, and they diagnose you with something they don't consider an "emergency," like general soreness or mild whiplash, your PIP benefits are capped at just $2,500.

An EMC is generally defined as medical symptoms so severe that without immediate attention, you could face serious jeopardy to your health or serious dysfunction of a body part.

This is where delayed neck and back pain gets tricky. If you go in days later and downplay your pain, saying "it's just a little stiff," a doctor might not categorize it as an EMC. But $2,500 burns up incredibly fast in the medical world; sometimes just a few diagnostic scans and therapy sessions will wipe it out.

In order for your doctor to accurately determine whether your pain and limitations meet the EMC threshold, it is imperative that you be completely honest with them.

I deal with insurance adjusters all day long. I know their playbook. When they see a file that says "no injuries reported at scene" followed by a gap of four or five days before treatment started, their eyes light up.

They see an opportunity to deny coverage.

They will use what we call the "causation defense." They will look at that gap in time between the crash and when you saw a doctor and argue that something else must have happened in the interim to cause your back pain.

They’ll suggest you must have tweaked your back carrying groceries, picking up your kid, or tripping on the sidewalk at home. They will try to argue that the car accident isn’t the cause of your current pain because you waited so long to complain about it.

When you have delayed symptoms, the burden of proof gets heavier. We have to work harder to medically connect the dots between the impact of the crash and the herniated disc or severe whiplash you are suffering from now. This is why having a lawyer in your corner early in the process is so critical.

Sometimes, delayed pain turns out to be something very serious. What felt like stiffness on Day 3 might turn out to be a herniated disc pressing on a nerve that requires surgery months later.

Obviously, $10,000 in PIP won't cover surgery.

When your injuries are severe, we have to step outside of the "No-Fault" system and file a claim against the at-fault driver's liability insurance for things like pain and suffering, future medical bills, and lost income capacity.

However, in Florida, you can't just sue for pain and suffering for minor bumps. You have to meet what’s called the "Permanent Injury Threshold." You need medical proof that you have suffered a permanent loss of a bodily function, significant scarring, or a permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability.

Delayed-onset back injuries often end up meeting this threshold, but it requires diligent medical documentation from the very beginning.

If you are reading this a few days after an accident and your neck or back is starting to hurt, please don't panic, but do act quickly.

Don't try to be tough. Don't worry about inconveniencing doctors. Your health and your financial future are on the line.

Go to an urgent care or see a specialist today. Tell them exactly when the pain started and that you were in a crash. Start a journal at home documenting your pain levels everyday and what activities you can no longer do.

And before you give a recorded statement to any insurance adjuster, even your own, give my office a call.

We know the tricks insurance companies use to devalue delayed pain claims. We know how to ensure your medical records tell the true story of your injury. Let us handle the complex legal timelines so you can focus on getting your back feeling right again.

I sit with the blinds half open, the humid Largo light laying itself across the desk, and I keep thinking about how a single turn of a wheel can remap a life. My name is David Carter, I run cases at Carter Injury Law, and I write about what I see in the quiet hours between calls and in the loud hours when an ambulance clears the intersection. This is a guide from my office to the street, a plain map of the laws that protect cyclists in Florida, and how I walk a client through the work that follows a crash.

Bicycles are treated like vehicles under Florida law, meaning riders have most of the same rights and duties as people in cars. That is the first legal fact I say out loud to anyone who walks into my office, because it changes how a case begins and how a jury will imagine the scene.

A few legal truths I repeat until my voice is tired

Anyone under the age of 16 must wear an approved helmet while riding or riding as a passenger. This is a statutory rule, not only a safety plea. The helmet rule matters for health, and it sometimes matters in how an insurance company describes blame.

Florida requires drivers to carry Personal Injury Protection coverage, PIP, which pays a portion of reasonable medical expenses and lost wages without waiting for fault to be decided. For many cyclists hit by cars, PIP is the first source of payment that gets scans and therapy going.

Florida uses a modified comparative fault system, which means a person who is more than 50% at fault cannot recover damages. Small percentages shift a case more than people expect.

The deadline to file most negligence claims is short now, and acting quickly preserves rights. The way I start each intake was altered by the law that reduced the negligence window to 2 years for claims accruing on or after March 24, 2023.

Wide roads and small margins characterize Largo. Cyclists carefully thread that afternoon, while drivers move as if they own it. My files show the same trends and problem areas. The hour before dusk, when light fades and a bike becomes more difficult to see, intersections where drivers make wide right turns and clip a wheel, and merge lanes where a shoulder check is unable to locate a rider. I bring those patterns into settlement negotiations because they influence plausibility, which in turn influences payment.

When a client calls me after a crash, I want a few clear things, because those things make the difference between starting strong and starting slowly. I tell every rider, plain and quick, the same list.

Move out of immediate danger, then call 911.

Get medical care, even if pain feels small. Notes and scans make the medical story clear.

Photograph the scene, vehicle positions, skid marks, crosswalks, road signs, and your injuries.

Collect driver and witness contact information, and note the time, direction of travel, and lighting conditions.

Preserve the bicycle and clothing. Do not wash blood out of garments until a doctor says go ahead.

Avoid giving recorded statements to an insurance company without counsel, and keep a log of missed work and daily changes in your life.

I give that list in the first conversation because it is where problems are most often solved, and because evidence lives in those first hours. Also, Florida law requires a police report when there are injuries or at least five hundred dollars in property damage, which is another reason calling the right people at the scene matters.

PIP is not a full answer, but it is an immediate one. In many bicycle collisions with motor vehicles, PIP pays a portion of reasonable medical bills quickly, up to statutory limits. That speed keeps treatment moving, which is something I value above a headline number.

When injuries are serious enough to exceed what PIP covers, or when the at-fault driver is clearly responsible, we move to a third-party liability claim to pursue recovery for what PIP leaves behind, including future care, lost earning capacity, and pain and suffering.

Nobody is perfect. Insurance adjusters love to point that out. In Florida, fault gets divided, and that division reduces recovery in proportion to responsibility. If a jury decides a cyclist is forty percent at fault, the cyclist receives sixty percent of the damages awarded. If a jury finds the cyclist more than fifty percent at fault, the cyclist recovers nothing.

That legal arithmetic is part of why I build cases not only with medical proof but also with scene reconstruction, witness statements, and clear narratives that explain why the driver’s choices led to harm.

If a driver leaves the scene after causing injury, the matter becomes criminal as well as civil. Leaving the scene can bring serious penalties, and that criminal record changes the dynamic at the negotiating table. I have worked cases where criminal charges helped a family secure better compensation, because a prosecutor’s file is proof of a different kind.

At the same time, when a driver is unknown, a thorough investigation into traffic cameras, plate readers, and cell phone records becomes a crucial part of building a claim.

The people I feel worst for are the ones who made avoidable errors in the first day or two. They are the clients who waited to tell their primary care doctor about a new pain or who gave an insurer a recorded statement the same afternoon. The list of avoidable mistakes repeats often enough that I make it part of every intake.

Waiting to see a doctor because pain is intermittent.

Letting the bike be repaired without photographing damage.

Deleting texts or failing to collect witness contact details.

Posting a running blow-by-blow about the crash on social media.

Believing PIP will cover everything without pursuing a liability claim when appropriate.

My work is a mix of craft and logistics. I gather medical records and bills, preserve bike repair estimates and photos, get depositions when necessary, and present experts who link injury to cause.

I talk with treating doctors about prognosis, and when surgery or long-term care is likely, I make sure that evidence is reflected in demand numbers. I also model lost earning capacity when a client cannot return to prior work. The record is what convinces an adjuster to shift or a jury to rule.

A successful claim can include payment for medical bills, future medical care, lost wages, lost earning capacity, pain and suffering, scarring or disfigurement, and loss of enjoyment of life. If an injury is catastrophic, I model lifetime care and lifestyle changes.

For families who lose a loved one, the rules and remedies change again, and wrongful death claims open a different door. The numbers alone never tell the full story, which is why I put weight on testimony about how an injury changes ordinary days.

I will be blunt about helmets. They save lives, and I tell that to parents and riders without theatrical language. Statute requires helmets for youngsters, and even if a helmet cannot undo an injury, it often helps in settlement optics. I also tell people not to sign anything offered by an insurer before they talk to a lawyer and to keep records of missed work, receipts, and the small changes the injury imposes on daily life.

If you want someone to read a report, an imaging study, and a set of photos, I will read them line by line. I will tell you plainly what the law can do and what it cannot. I will build a case that respects the facts and the person who lived them. This work is about repairing what can be repaired and making sure obligations fall on the people who made the choices that caused a crash.

If you were hit in Largo, bring the police report, photos, and medical records. I will look at them and then tell you what we can do next and how we will carry the cost of care while we pursue the rest. The road back is not quick, but it is winnable when actions are taken early and when the right evidence is preserved.

I grew up here, and I live here, where the Gulf light makes everything look softer than it is, and where folks hurry from work to practice to the beach and back. I also practice injury law in Largo, and I have watched good people make the same small, human mistakes after a crash. Those mistakes do not feel dramatic at the time. They feel like choices meant to keep life moving. Later they are the reasons a claim shrinks or a benefit is denied.

Below I write in first person, the way I explain things to the people who sit in my chair. I will name the five culprits I see most often, give plain steps to avoid them, and close with a short glove box checklist you can use the next time the unexpected happens.

People here shrug and say they are fine. They do not call the police, they do not insist on a crash report, and they do not go to a doctor. That quiet pride looks courageous in the moment, but it is costly later. In Florida, official records and early medical entries shape whether insurance pays, and if you miss those records, an insurer will say there is no proof your injuries are related to the crash. The state expects you to treat evidence like something fragile, not optional.

What I tell clients in plain language, and what you can do at the scene:

Call 911 if anyone is hurt or if damage looks serious. Get the police report number.

If an officer does not come because damage seems minor, file a driver report of the traffic crash or get a copy of the crash report later through the state portal.

See a medical provider within the first two weeks if you feel anything at all, even soreness. Florida law ties some benefits to that early treatment window, and the records will be the clearest story of what happened.

Someone will offer to take care of your car, to tow it to a shop they recommend, or to get you a speedy estimate. Folks often accept this because it sounds like help and because life is already messy after a wreck. The problem is control leaves your hands. Estimates can be cooked, photos can be lost, and you may sign a release you did not read.

How I counsel clients to safeguard themselves:

Photograph the scene, the damage, the license plates, and the location before anything is moved.

If a tow arrives, write down the tow company name, the driver name, and the lot address. Keep copies of any keys or receipts.

Do not sign anything that releases your right to further inspection or medical review. Keep the car where you can document its condition until you get independent estimates.

Largo gets tourist traffic, weekend drivers who do not know a merge on Ulmerton from a merge on Seminole Boulevard, and commuters who are in a hurry. Locals assume familiarity breeds clarity, and so they let the other driver walk away without collecting witness names or confirming insurance details. Later, the evidence that mattered is gone with that other driver.

My plain rule for clients:

Treat every crash like a formal event, even if you know the other driver. Write down names, license plate numbers, insurance companies, and policy numbers. If witnesses stays, ask for a phone number.

If the other driver leaves or seems evasive, note that, take photos of the scene quickly, and tell the responding officer everything you recall. The small details you collect then will be the facts we rely on later.

Adrenaline is a hard thing. I have had clients who drove themselves home, went to work the next day, and then months later learned they had an injury that complicated everything. Florida law and insurance practices put weight on the timing of medical care. Waiting to seek treatment weakens both care and compensation.

What to do:

Go to urgent care or your doctor within days if you feel pain, stiffness, numbness, or any new symptom after the crash. Keep every bill and every note.

Follow the treatment plan your clinician gives you, even if it feels slow. The record of care, and your adherence to it, is evidence.

If you are unsure where to go, an ER visit is safer than silence.

People here are social. We post the sunset, a kid at the park, and a barbecue with friends. I have seen social media posts and casual conversations pulled into a file and used to argue someone was not hurt. I have also watched clients give recorded statements to the other side without counsel, thinking they were only being polite, and then feel the consequences later.

You are not obliged to give the other driver’s insurer a recorded statement, and your own policy may ask you to cooperate in an investigation, but that cooperation is different from a free-form interview that can be used against you. Handle recorded statements with care, and pause your posts for a while.

Steps I recommend:

Stop public posting about the crash, recovery, or activities that show fitness or travel. Do not accept friend requests from unfamiliar accounts.

Give insurers only the basic facts they need for processing, and tell them you will consult counsel before giving a recorded statement if the other side asks for one.

Keep a private log of symptoms and limits, with dates and short notes. Those notes help make sense of the medical record later

Two legal points I always explain to clients because they change decisions in the first week after a crash. First, the early medical window matters for Florida PIP benefits, and failing to seek care within that window can cost you covered treatment. Florida law ties PIP to early treatment requirements.

Second, the deadline for filing a personal injury lawsuit in Florida can be short, and missing it can end your options. The state’s limitation rules require you to act within the period the law sets, and waiting because you think you will handle it later is not a safe bet. Check the specific deadline that applies to your case, because these timelines determine whether we can file at all.

Keep a printed copy of these in your car. I give this to clients the first day they walk in my office.

Safety first, then the facts. Call 911 if anyone is hurt. Move to safety if you can.

Photograph everything, even if you think it is minor. Close-ups of damage, wide shots of intersections, license plates, and traffic signals.

Get names, plates, insurance information, and at least one witness phone number.

Ask for the officer and crash report number, or file a driver report if no officer responds.

See a doctor within days, and keep every medical note, bill, and instruction.

Do not post details on social media. Do not give recorded statements to the other side without legal advice.

I represent people in Largo, but I am also your neighbor. The sun and the coffee and the sound of kids at the park are things I want my clients to get back to. Most of the damage I see after crashes is preventable with small, sober steps taken in the first minutes and days, the same minutes when life is loud and you want to rush on.

If you have been in a crash and you are worried about what to do next, reach out to us, who know Florida practice and Largo roads. A short call in the first week can keep your evidence intact, guard benefits you may be owed, and make sure the small choices you make now do not become big losses later.

I have walked the sidewalks off Ulmerton Road, and I have sat in waiting rooms at Largo Hospital, watching how a single turn at a traffic light rearranges a life. I write from here as someone who has answered calls at midnight from riders whose world has just turned upside down.

The difference between a minor injury claim and a major one shapes everything that follows, from what a doctor prescribes to whether a family can hold a mortgage and keep a child in school. This piece stays local, practical, and plain. It will name what I see, what I do, and how people in Largo can protect what matters most after a motorcycle crash.

A minor claim usually closes the book on the immediate chaos. It covers broken days at work, bills from a small ER visit, therapy for a stiff neck, and a settlement that lets someone move on. A major claim arrives like a tidal change. It involves surgeries, long-term rehabilitation, adapted homes, lost earning power, and legal proof that reaches into a lifetime.

The stakes are emotional and financial. Families rearrange budgets and futures, and as a lawyer I must build a case that not only tallies bills but also explains how a person has been changed.

When a claim is minor, insurance companies see numbers they think they can resolve quickly. When a claim is major, insurers see uncertainty and exposure, and they push back. Knowing which path you are on helps you choose medical care, evidence, and a legal strategy that fits the true cost of the injury.

I call a claim minor when the injury is temporary and the future looks like a return to work and everyday life. Examples I see in Largo include:

Soft tissue injuries such as sprains and strains

Minor fractures that heal without surgery

Concussion or mild traumatic brain injury with rapid recovery

Treat and release ER visits followed by short-term outpatient care

For a minor claim, the medical path is usually short. Initial care might be an ER visit at Largo Hospital, an X-ray, a short course of physical therapy, and a return to full duty within weeks or a few months. Documentation matters even in small cases. I ask clients to gather:

ER and urgent care records

Follow-up notes from primary doctors or physical therapists

Pay stubs showing days missed from work

Photos of injuries and damaged motorcycle

Proof of impact remains the same as in larger cases, only simpler. Medical bills, employer records, and clear treatment notes let us show loss and negotiate a settlement without prolonged litigation.

A major claim is one that changes the shape of daily life. I have sat with families while they stared at life care plans that list surgeries, home care, and years of therapy. Typical major injuries include:

Severe fractures requiring multiple surgeries

Spinal cord injuries with paralysis or long-term impairment

Moderate to severe traumatic brain injury with cognitive or personality changes

Amputations or injuries leading to permanent disability

The medical path for major injuries is long and layered. It often begins with a trauma admission, followed by surgeries, inpatient rehabilitation, specialty outpatient care, and sometimes lifelong support. For these claims we develop a life care plan, and we work with

Neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons

Rehabilitation specialists and physical therapists

Vocational experts when work capacity is affected

Life care planners who estimate future medical and personal needs

When a claim will affect future earning ability, the legal valuation must include past medical costs, future medical costs, lost wages to date, future lost earning capacity, and compensation for pain, suffering, and loss of life quality. That requires careful, documented proof.

Whether the injury is minor or major, establishing fault begins at the scene. In Largo I tell clients to do the practical things they can do safely. Call 911. Get checked by medics. Exchange information with the other driver. If you are able, take photos of the scene, the vehicles, skid marks, and visible injuries. Get witness names and a police report number. The Largo Police Department makes crash reports available to involved parties, which helps start the paperwork.

For major claims we go deeper quickly. Accident reconstruction may be needed when liability is disputed or the sequence of events is complex. Medical experts translate clinical findings into clear testimony about cause and prognosis. Vocational and life care experts explain what daily life will look like and how much future care will cost. For minor claims we rarely need that suite of experts. Clear medical records and consistent treatment are usually enough.

Insurers treat claims by size. For smaller claims they often open with quick offers that look tidy in a spreadsheet. Those offers can be tempting because they end uncertainty fast. I advise clients to remember what is not yet known. Untreated soft tissue injuries can become chronic, and an early low settlement removes leverage.

For major claims insurance companies stall, ask for recorded statements, and dispute projected future costs. They may hire their own experts to minimize liability or future need. My response is methodical. We document everything, and we present evidence in a way that a jury or mediator can understand, using reports from treating doctors and independent experts when necessary.

Timing matters here in a literal sense because Florida law tightened deadlines in recent years. The state passed reforms that reduced the statute of limitations for most negligence claims to 2 years from the date of injury for incidents occurring after March 24, 2023. This change compresses the window for filing suit and makes early action more important. I track filing deadlines closely so that we never lose the right to bring a case. (Florida Senate)

My practical checklist for the first 72 hours after a crash is short and specific:

Seek medical attention and get all records

Report the crash and obtain the report number from Largo Police or Pinellas crash portals.

Photograph the scene and your injuries when safe to do so

Preserve evidence related to lost earnings, such as pay stubs or employer notes

Call a lawyer to protect your rights and to coordinate evidence gathering

For minor claims my short-term strategy is documentation and negotiation. For major claims, my long-term strategy is building a full medical and economic record, preparing expert reports, and being ready to litigate if necessary.

I have watched perfectly viable claims derail because of small missteps. Common problems include:

Delaying medical care, which creates gaps in treatment notes and weakens causation evidence

Speaking to an insurer without advice, especially in recorded statements that can be used against you later

Failing to track lost income or ongoing symptoms that seem small but add up

Avoiding these mistakes preserves options. Even in minor cases, small details make a difference.

If you need urgent care in Largo, HCA Florida Largo Hospital provides emergency and specialty services and is a place I trust to document acute injuries and to begin treatment. (HCA Florida) For crash reports and initial police records, the Largo Police Department can provide an official accident report to involved parties. Pinellas County also maintains crash report services and investigative units that respond to serious collisions.

If a case will be long-term, we coordinate with local rehabilitative services, outpatient specialists, and regional trauma centers that handle complex recovery. That practical map of care matters when a jury or insurer asks how we will meet future needs.

When you call Carter Injury Law for a minor claim, I will:

Take the immediate facts and line up medical records

Communicate with the insurer to preserve your rights, while avoiding recorded statements that could harm you

Negotiate a fair settlement that covers bills and lost wages

When a claim looks major, I will:

Immediately secure and preserve evidence and medical documentation

Retain specialists to prepare life care and vocational reports

Work with medical providers to capture future care estimates, and prepare for litigation if needed

In every case I try to make the legal work a shelter, not another fight. I want clients focused on recovery while we build the record the case needs.

Largo is where I live and where I have learned the contours of these injuries. A motorcycle crash changes not only the rider but also the people around them. The legal difference between minor and major claims is not a technicality. It is a map of what the person and their family will need next. If you are injured, act sooner rather than later, document carefully, and reach out for help so that your claim reflects the real costs of what happened. If you call my office, I will sit with you, look at the paperwork, and outline the steps we need to protect your family and your future.

I write this from the passenger seat of my memory, the kind that keeps playing back memories of a metal scrape, the damp shine of rain on pavement, and the abrupt, gradual silence that follows impact. If you live in Largo, you are familiar with the city's roads and how a single crossing can change a person's life.

I am with Carter Injury Law, and I have stood with people who felt their world tilt after a truck struck them on US 19 or on Ulmerton Road, the arteries that carry heavy traffic through our neighborhoods. Those corridors are where accidents happen more often, and they shape how we investigate and fight.

Largo is not an abstract place in a headline; it is a town with names, errands, and a rhythm of delivery trucks and big rigs pulling through to points north and south. When a commercial vehicle looms into a lane where a family drives home from work, the consequences are a mother who cannot work, a father who learns how to call doctors between breaths, and a child who remembers the sirens.

I have watched insurance companies reduce stories to forms, and I have learned that the details of place change the work we do. Knowing which road a crash happened on, what the light cycles were like, and who was responsible for the load is the difference between a claim that stalls and one that moves toward justice.

In my work I see patterns cut across individual tragedy. Driver fatigue from long shifts shows itself in late-night lane drift. Cargo that is not secured becomes a projectile at speed. Turning maneuvers, unfamiliar routing, and maintenance failures leave traces that an experienced investigator can read.

The more you document at the scene, the better we can put the pieces together later. Federal and state rules govern commercial carriers, and those rules shape the evidence we gather, from hours of service logs to maintenance records.

I speak to people when their hands are still shaking. Do what you must for health first, then for the record. If you can, keep these steps in mind and act on them, because the smallest photo can become the clearest proof.

Call for medical help and call Largo police. Use Largo Police communications at 727 587 6730 for a report. Always dial 911 in emergencies. The police report will be an early and essential document in any claim.

If you can, photograph the scene from several angles, showing damage, skid marks, signage, and the relative positions of vehicles. Record the truck number or carrier name if visible.

Get witness names and contact information. A short voice memo of what a witness saw is better than no witness at all.

Seek medical attention, even if you feel fine. Injuries can declare themselves hours or days later, and medical records create a timeline that supports your claim.

Preserve any receipts, towing reports, and medical bills. Do not accept a recorded statement from an insurer without legal counsel, because that statement can be used against you.

Contact a local truck accident lawyer who understands commercial carriers and the way their insurance works. We begin an investigation right away, collecting driver logs, maintenance records, and background on the carrier to make sure nothing disappears.

Being local matters. I know the officers on the beat, the county teams that respond to complex crashes, and the courts where these cases move. Pinellas County has a Major Accident Investigation Team that investigates serious collisions, and their findings can be vital in building a case.

Working with local investigators and knowing where to look in county records saves crucial time. That local knowledge is how we keep an insurer from ruling the conversation by making the first move.

We begin with listening, because legal work is human work. I meet clients, I take careful notes, and my team moves to preserve evidence. We subpoena driver logs and maintenance files, we reach out to witnesses, and we use the police crash report as a foundation for a broader reconstruction when needed. We negotiate, and we stand ready to prove a case in court when insurers dig their heels in.

We also handle the practical things that become heavy for an injured person. We coordinate with medical providers, we help arrange for records, and we explain what the claims process looks like in plain language. We have experience with delivery truck claims, where responsibility can lie with a driver, a carrier, or even a manufacturer, and those claims require a deeper, layered approach. At the center of the work is a promise to treat each file like a person, because the file is a life. (carterinjurylaw.com)

When the dust settles, a claim can include medical costs, lost wages, damage to property, and what the law calls pain and suffering. In wrongful death cases the law creates a path for the family to seek accountability and damages.

The deadlines under Florida law are strict, and most personal injury and wrongful death claims need to be filed within two years from the incident or death, unless an exception applies. That timeline is a part of why early legal contact matters.

I answer these questions every day at intake, and I answer them here with directness and care.

If an insurer calls immediately, you may tell them you will speak with your lawyer first.

If the truck driver says it was my fault, the driver’s statement is not the end of the story. We gather more evidence.

If you cannot work, keep records of lost wages and a letter from your employer.

If the crash involved a commercial carrier, federal records and driver logs can show whether rules were broken.

If the worst happens and death occurs, the family’s claim must be filed promptly under Florida deadlines, and we provide a compassionate guide through that process.

I once met a woman who returned to find her car a crumpled outline at the side of Ulmerton Road. She was alive, but the insurance calls had already started. We photographed the scene, obtained the truck maintenance records, and worked with the Major Accident Investigation Team notes to show the carrier had failed to secure a load.

The case settled for the damages that mattered to her, and she was able to focus on recovery. I tell the story not because every case is the same, but because clear records and timely steps make outcomes possible.

When the sirens fade and forms remain, the work of justice is slow unless someone moves it. I do this work because I have seen families pushed to the edge by medical bills and by grief, and I know that a careful, local approach can return dignity and resources. If you were hit on a Largo highway, you do not have to carry the aftermath alone.

We will gather the evidence that speaks for you, we will keep the paperwork moving, and we will fight for the compensation that lets a family breathe again. If you want a printable checklist or help starting the paperwork, I will help you begin today.